A sustainable luxury resort in a desert?? Sounds like an oxymoron, doesn’t it? But, Jaisalmer is home to luxurious palaces and exemplary urban design, which, are well adapted to the harsh arid climate without reliance on air-conditioning and water for thermal comfort.

With such time-proven sustainable design strategies at hand and modern technology, the proposed resort design set out to achieve these seemingly disparate goals.

What makes sustainable design in the desert particularly challenging is that –

– The sun and heat, plentiful in the desert, have to be kept out.

– Cooling elements such as trees and water are in short supply.

But the city of Jaisalmer, has dispelled the notion that an abundant supply of water and vegetation are necessary to create a vibrant, beautiful and – the now trendy phrase – sustainable design.

Jaisalmer:

When Jaisal Singh built his new capital city, Jaisalmer, in 1156 A.D. on the western fringes of India’s Thar desert, he did not think of damming and diverting rivers to sustain his home and his people, like we do now to feed our golf fixes and arid farmlands.

Instead, the city and the proposed design use elements such as:

– thick masonry walls

– narrow streets

– assymmetric volumes

– contiguous low-rise courtyard dwellings

– cantilevered building floors

-screened windows

-wind scoops,

-wind towers

to perform the double duty of creating a dynamic built-scape along with achieving a milder micro-climate within the walled city, and proposed design complex, and cooler and relatively stable temperatures inside the buildings, by incorporating-

-Thermal Lag

-Shade

-Ventilation

Proposed Design:

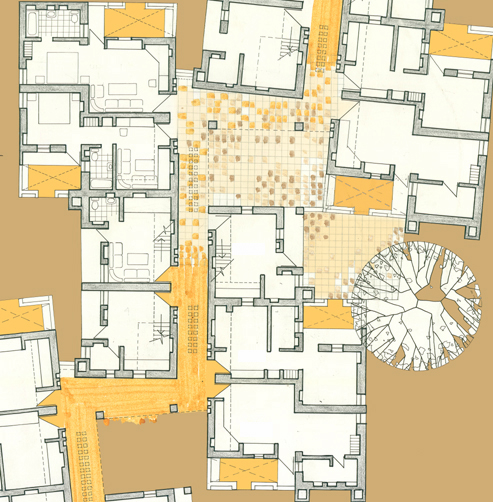

In addition to incorporating existing passive cooling strategies, the proposed design re-interpreted the city, as a cluster of air-conditioned guest blocks on the north east ridge of the site, and Jaisalmer’s surrounding adobe villages of Sam, as an earth-sheltered “village” of non-air-conditioned guest rooms. The public services were located between the “city” and the “village” of the resort to facilitate access, transition and operation.

PASSIVE COOLING STRATEGIES:

Thermal Lag:

Thick masonry walls of local sandstone in the lower floors were built as security devices in Jaisalmer, but they also reduce conductive heat gain by delaying the transfer of heat from the outside to the inside. Heavy materials such as water, adobe, stone, and concrete take much longer to heat up and keeps the interior surfaces cooler for a much longer time than lighter materials such as wood. This phenomenon is known as thermal lag. The principle of thermal lag works differently from insulation, which reduces the heat conducted instantaneously to the interior surface due to temperature differentials between the inside and the outside, in that it actually creates a time delay in transferring heat from the outside to the inside. The extent of the time delay depends on the heat capacity and thickness of the material.

In Jaisalmer, the thickness of the walls (up to 4’ in some places) along with the heat capacity of the local sandstone, delay the heat transfer to the inside by 8-12 hours, so that the low night-time temperatures reach the internal surfaces around the middle of the day, cooling the inside air down.

Thick masonry walls of local sandstone in the lower floors also aid in keeping the building interiors cool by damping the diurnal range of temperature. The degree by which the material dampens the diurnal swing is called the decrement factor. In Jaisalmer, the masonry walls dampen the external temperature extremes of over 43 deg C during the day and near freezing at night, to a reasonably steady internal temperature, with little variation between day and night time temperatures.

In the proposed design, the air-conditioned guest rooms have stone masonry combined with insulation to reduce thermal load on the air-conditioning systems, while the non – air conditioned rooms are made of thick walls of rammed earth and are partially earth-bermed to take advantage of the earth’s thermal mass and transfer its stable temperatures to the interior of the guest rooms.

Shading:

One of the obvious steps to minimizing direct solar heat gain is shade, shade, shade and more shade. This is achieved by creating a seemingly erratic mix of solids, voids (courtyards), and overhangs, which creates self-shading along with a dynamic cityscape.

At the building level in Jaisalmer, and the proposed design, the built volume gets progressively lighter from the ground up. Unlike the lower floors, which have thicker walls for thermal lag and are completely shaded by the upper cantilevers, the indented and intricately carved stone facade is a clever adaptation to create a finned surface that reduces direct solar heat gain by creating pockets of self-shade for cooling, while losing heat from the entire surface at night, causing a net increase in the relative surface area for heat-loss over heat gain.

Ventilation:

At night, ventilation is the primary mode for heat loss.

Air movement is just as necessary as cooling to achieve thermal comfort, in extremely hot places such as Jaisalmer. Ventilation extends what is called the thermal comfort range, by increasing the rate if evaporation from the skin, and heat removal through convective heat transfer from the building.

Pressure differentials created between completely shaded and partially shades open spaces in Jaisalmer and the proposed design, induce air currents – through the courtyards, buildings and streets. At the building level, courtyards, wind pavilions and the intricately carved fenestration screens induce air movement while filtering the sand particles out.

In addition, the curved top of the wind-shaft in the proposed design creates a low pressure zone that draws warm air out of the room while drawing in cooler air from the shaded courts.

All the non-air-conditioned rooms were earth-sheltered and ventilated through wind scoops, whose slanted opening is designed to capture the desert winds, and the wetted charcoal mesh filters and cools the wind, before it enters the earth-sheltered room. The warm air of the outside assists in drawing the cool air out of the room through ventilators placed high above the room.

The landscape uses a small water channel to unify the space and cool the air before it is drawn into the system of courts, a drip irrigation system and native plantation, to conserve water, and provide some relief from the hot desert sun.

Dear Aditi Raychoudhury and Professor Chauhan,

The observational and monitoring work which led to the design techniques in these designs are well displayed in these plans. We have been considering installing downdraft evaporation cooling towers for our ecocampus [www.tinyurl.com/ecocampus and http://www.youtube.com/kibbutzlotan ] and upcoming natural building construction projects. I have seen large systems (towers that are 12 meters high cooling large rooms). I wonder if your proposed design would actually work with such a short tower (5-6 meters, 1 m diameter, ~20 sqm room) I would like to know what is the smallest system has been constructed and is in use to learn how to transfer this technology to our region and share with our students.

thank you,

Alex Cicelsky

Center for Creative Ecology

http://www.kibbutzlotan.com/ga

LikeLike

Hi, Alex,

This was an undergraduate design thesis, and hence, the exact engineering calculations were not expected. In my graduate program, I focussed on engineering aspects of energy saving measure and passive solar technologies. However, I didn’t study the size and shape of cooling towers for my undergrad thesis at the time.

LikeLike

PS: You could contact one of the following institutions in India and see if you get more help.

Development Alternatives, New Delhi

TERI, http://www.teriin.org/index.php

Solar Energy Center, http://www.mnre.gov.in/centers/about-sec-2/contact/

hope this helps.

My apologies for the delay in response.

LikeLike

Heartiest congratulations for an excellent design. The project is conceived most appropriately learning from the traditional architecture of Rajasthan.

I do hope that you have continued your research and are using the same in your practice. Would like to know more about your research and works.

Please contact:

Rizvi College of Architecture, Off Carter Road,

Bandra West, Mumbai 400 050 India.

EMail: rizviarchitecture@gmail.com

LikeLike

Hello, Professor Chauhan,

Thank you for your kind words and I apologize for the delay in getting back to you.

I haven’t done any research on desert architecture lately and have been focussing on writing children’s books. I did spend nearly a decade working in San Francisco, California, on energy efficient building design.

If you have specific questions, or would like to know more about the references I used for my project, I will be very glad to help.

India has changed a lot since I left, and I put down some of my thoughts about the current “international” trend in architecture in one of my blog posts.

https://lunaspace.wordpress.com/2007/08/16/oceans-away-our-new-homes/

LikeLike

Hello, Professor Chauhan,

Thank you for your kind words and I apologize for the delay in getting back to you.

I haven’t done any research on desert architecture lately and have been focussing on writing children’s books. I did spend nearly a decade working in San Francisco, California, on energy efficient building design.

If you have specific questions, or would like to know more about the references I used for my project, I will be very glad to help.

India has changed a lot since I left, and I put down some of my thoughts about the current “international” trend in architecture in one of my blog posts.

https://lunaspace.wordpress.com/2007/08/16/oceans-away-our-new-homes/

LikeLike